This post contains affiliate links, meaning I get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through my links, at no cost to you. Please read my disclosure page for more details.

Category: French History

This episode features our frequent and very popular guest Elyse Rivin. If you enjoy her episodes, please consider supporting her on Patreon.

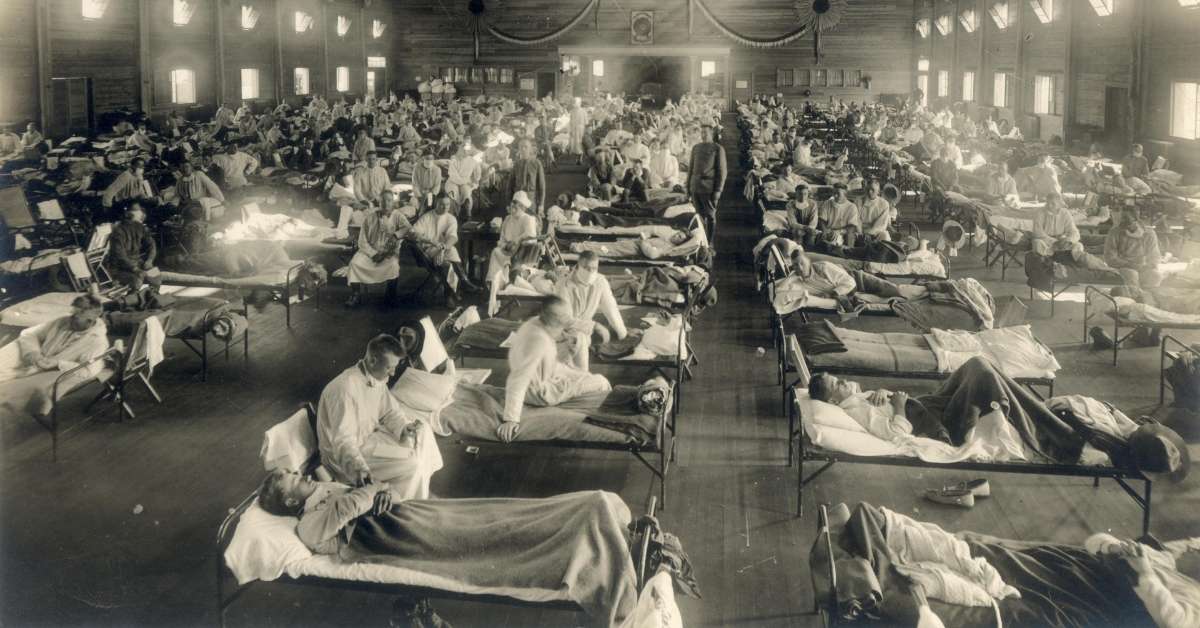

On today's episode of the podcast Annie Sargent brings you a conversation with Elyse Rivin. As we celebrate then end of WW1 it is also important to remember that the Spanish Flu killed even more people than the war that had just ended. We also talk about how the Spanish Flu changed Europe forever especially how Europeans understand the need to extend health care to everyone.

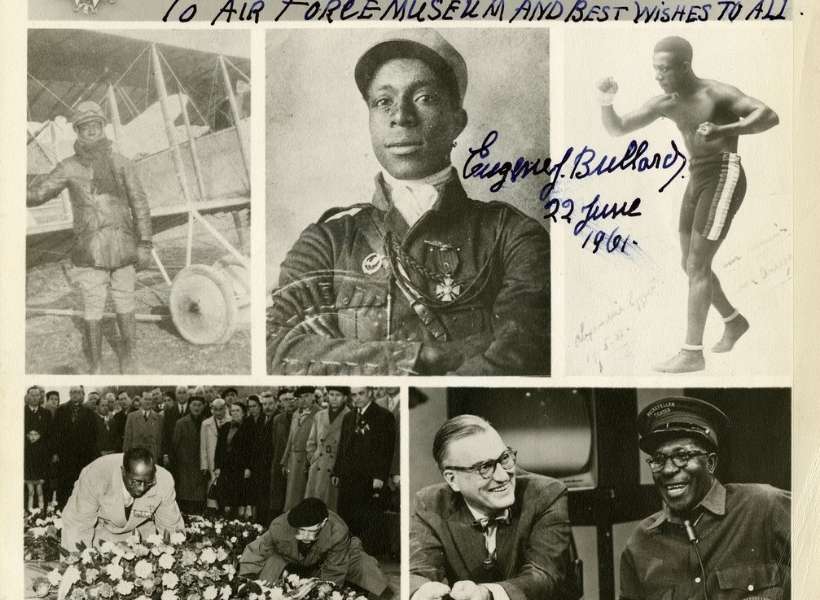

I also want to do a quick review of a book about WW1 that I absolutely loved called All Blood Runs Red by Henry Scott Harris about Eugene Jacques Bullard the African American born in Georgia who enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and served with great honor in both WW1 and WW2. An extraordinary person and a well crafted book that brings WW1 and this person to life for me.

I will also read you a bit of The Plague by Camus right before the end music. If you're interested in learning about virology today, Annie recommends you add This Week in Virology to your podcast line-up.

Remembering the Spanish Flu

Unfortunately talking about the Spanish Flu is the right way to celebrate WW1 in 2020 because we're in the middle of our own pandemic right now.

It is called the Spanish Flu, but it had little to do with Spain. This flu didn't start in Spain. They had no part in spreading it any more than any other country. What happened is that since they weren't involved in WW1 Spanish newspapers were not the victim of censorship. They spoke about the pandemic freely in Spain and so they got associated with it for no reason.

It is more likely that the Spanish Flu started with a farmer in the US who then went to serve on a US army base. As American soldiers were shipped out to help end WW1 they spread the virus all over the world. The first place these soldiers landed was in Bordeaux and it spread from there in France.

The Spanish Flu was a very effective virus and spread quickly. Viruses affect humans with zero care for their nationality. That's why it's unfair to call it a Spanish flu or an American flu or a Chinese flu. Humans are subject to viruses and that's what matters.

The first wave of Spanish flu (May 1918) was not particularly deadly, the second wave was awful (the fall of 2018) and the third a bit less virulent. But by then the flu had spread all over the world, which is the definition of the word pandemic. The Spanish flu killed about 4% of the people it infected, and it was mostly younger people who go sick with it.

In the US there were pro mask cities and anti mask cities and, predictably, the cities like San Francisco where masks were seen negatively had more deaths.

The Plague by Camus

Every time there is a pandemic there is a great temptation from political leaders not to scare the public and brush it under the rug. Albert Camus was writing about a fictional plague but he brought that fact into his famous book. Annie reads this part of the book at the end of the episode.

The local press, so lavish of news about the rats, now had nothing to say. For rats died in the street; men in their homes. And newspapers are concerned only with the street.

Meanwhile, government and municipal officials were putting their heads together. So long as each individual doctor had come across only two or three cases, no one had thought of taking action. But it was merely a matter of adding up the figures and, once this had been done, the total was startling. In a very few days the number of cases had risen by leaps and bounds, and it became evident to all observers of this strange malady that a real epidemic had set in. This was the state of affairs when Castel, one of Rieux’s colleagues and a much older man than he, came to see him.“Naturally,” he said to Rieux, “you know what it is.”

“I’m waiting for the result of the post-mortems.”

“Well, 1 know. And I don’t need any post-mortems. I was in China for a good part of my career, and I saw some cases in Paris twenty years ago. Only no one dared to call them by their name on that occasion. The usual taboo, of course; the public mustn’t be alarmed, that wouldn’t do at all. And then, as one of my colleagues said, ‘It’s unthinkable. Everyone knows it’s ceased to appear in western Europe. Yes, everyone knew that — except the dead men. Come now, Rieux, you know as well as I do what it is.”

Rieux pondered. He was looking out of the window of his surgery, at the tall cliff that closed the half-circle of the bay on the far horizon. Though blue, the sky had a dull sheen that was softening as the light declined.

“Yes, Castel,” he replied. “It’s hardly credible. But everything points to its being plague.” Castel got up and began walking toward the door.

More episodes about French History

FOLLOW US ON:

Subscribe to the Podcast

Apple YouTube Spotify RSSSupport the Show

Tip Your Guides Extras Patreon Audio ToursIf you enjoyed this episode, you should also listen to related episode(s):

- WW1 Memorial Sites in France, Episode 211

- Chateau-Thierry and the Battle of Belleau Wood, Episode 256

Category: French History