Categories: Arts & Architecture, French Culture

Rosa Bonheur — Artist — (1822-1899)

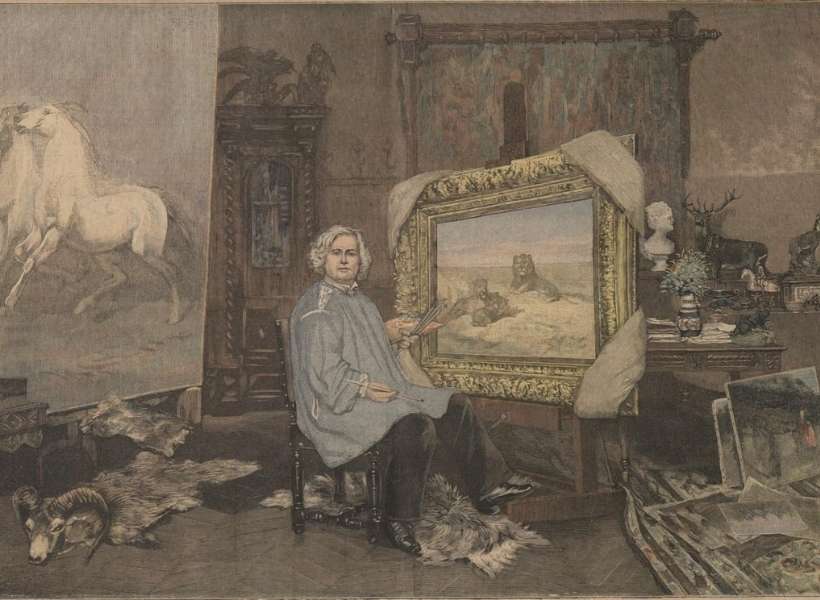

Rosa Bonheur was one of the most successful painters of her generation and was the most important and successful woman artist of the 19th century. Known for her paintings of animals and for her eccentric and somewhat exotic lifestyle, she was a consummate artist who lived a singular life.

When people who know about art and painting hear her name, what immediately comes to mind is that she painted animals. They were the passion of her life. But her work is so much more than ‘just” painting animals, and the why and how of her becoming an artist are part of an incredible story.

One of the things that makes her special is that she was, from the beginning of her career, in a category of her own. Unlike most of her fellow women artists, she was never put into a box as doing “women’s art”, and neither was she fully accepted or considered to be equal to the men artists of her time.

Interestingly, like some other famous women artists in the past, she became an artist partially because her father was one: in fact, he was her sole art teacher and began teaching her to paint and draw when she was a child. Her father was an artist and also director of an art school for ‘young women’, who were not allowed to attend the Fine Arts schools at that time. He knew many artists, even apparently Francisco Goya, the famous Spanish artist who was exiled in Bordeaux where Rosa’s family lived.

And he encouraged Rosa, as well as her siblings, to pursue art as a career. He in turn, was influenced by a strange movement called the St Simeonism, which preached the good of progress and invention, and, among other things, that women had the same capacities to have the same opportunities as men.

Turbulent and having difficulties at school as a small child, her mother, a musician and somewhat poetic, invented a system of associating a letter with an image of an animal as a way of teaching Rosa to read. She said later on that this imprinted in her the idea that animals were necessary to her as a means of expression, and although she could do portraits and other kinds of scenes, she very quickly concentrated her artistic abilities on doing” portraits” and scenes involving animals, with or without humans.

Working from home, devoting her time to art, by the age of 17 or 18 she was already doing large, sophisticated paintings of animals with an astounding amount of realism. Two things that helped influence her besides the ideas and teachings of her father were the advent of photography, which she used, and the reading of some of the novels of the writer George Sand, who was a woman writer who often wrote stories about the countryside and the life of peasants and their animals. However, unlike George Sand who took a man’s name as a “nom de plume” to get published more easily, Rosa Bonheur never tried to be anyone other than herself. Among the influences on her work, were the writings of a theologian named Félicité de la Mennais, who believed that animals had souls. So, without much doubt or hesitation, she made her life’s work, the depiction of animals in both intimate and heroic scenes.

Rosa Bonheur had a quick and phenomenal success as a painter. At the age of 19 she had a large painting admitted to the official Salon of 1841 (these were selective juried shows). Then in 1845 won a 3rd place medal for one of her paintings. And finally, in 1848, won 1st place prize for one of her now very famous paintings, “Boeufs et Tauraux, Race du Cantal”. (Steers and Bulls: Cantal Breed). The jury and the public were so impressed by the detailed and powerful realism of this work, that she was soon contacted by the government and was given a commission, a command, to do an agrarian painting, for which she was paid 3000 francs, a nice sum for the time.

This painting, “Labourage Nivernais”, was a huge success. It made her famous. At her death it was given to the Louvre, and then in 1986 it was sent to the Orsay museum where it can still be seen. At the death of her father in 1849, when she was 27, she took on the role of Director of The Imperial School of Design and Drawing for Young Women and kept this job for a very long time. So all the time she was painting and sculpting, she was also teaching.

In 1853 she painted what is considered by some to be her masterpiece, Le Marché aux Chevaux, The Horse Fair, which belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of New York. The painting, which is over 16 feet across and is 8 feet high, is an incredible image of a group of horses being paraded for spectators to see, as they are put up for sale. The work is extremely powerful and dynamic. Here is what a contemporary art critic said of it; “… it is really a man’s painting: nervous, solid, free of artifice. It is neither a Romantic work nor a Classical work. It is unique.” This, of course, was the ultimate compliment: it looked like it was painted by a man! This painting became so famous that it was taken to England, where it was bought by a rich merchant and then shown in London. Queen Victoria even asked for a private showing of the painting, as she was passionate about horses. It eventually was bought by the immensely rich American, Cornelius Vanderbilt and was donated by him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York where it has been ever since. *

From 1855 the works of Rosa Bonheur were admitted to all the major Salons (major shows) without having to pass by a jury, something that very few artists were allowed to do, man or woman. And by 1856 her work was all sold out as soon as it was done, so that she no longer worried about her finances. She became an incredibly successful artist from a financial perspective.

Here is what another male art critic had to say about her work: ‘with her (Rosa Bonheur) there is no need for gallantry, she does her work seriously, and she can be treated like a man…painting is not for her a question of delicate little touches like embroidery.” This of course, was how most women artists, even those recognized as being talented, were considered at the time.

In 1860 she bought a little chateau, in the town of Thoméry, where she set up a real menagerie and where she could paint, looking out at the farmlands and the animals nearby. She spent hours observing animals and their innards in a slaughterhouse to make sure she had the anatomy correct. There was nothing about an animal; in its physical qualities and behavior, that she did not know or like.

In 1865 Rosa Bonheur had the privilege of being awarded the Medal of Chevalier of the Legion of Honneur. This honor was offered to her by the Emperatrice Eugenie, who had become a friend of hers and who visited her home and atelier several times. She was the very first artist, and the ninth woman to be awarded this great honor.

Rosa Bonheur had a supreme confidence in her work and was a tireless promoter of her art. She was also an early proponent of Female Emancipation and was one of only a few women given ‘official’ permission to wear men’s clothing, to wear trousers, and to smoke a cigar. (The French law that forbade women from dressing like men was only officially made nul and void in 2013!) She lived a totally unconventional life and clearly was never worried about what society would think. She had a life-long woman companion, who also helped her with her artwork and due to her incredible self-assurance and her financial independence, cared not a bit what people thought of her way of living. Largely because her choices had been accepted early on by her family, she was confident enough in both her talent and her life choices to not make any concessions.

Rosa Bonheur was internationally known by the 1870’s. She was very popular both in England, where she had made friends, and in the United States where her naturalistic paintings of farms and animals coincided with a ‘back to nature” movement. In 1893 she had four of her paintings and three lithographic drawings shown at the Universal Exposition in Chicago.

By the time of her death in 1899, she had entered the category of ‘untouchable’ artists; those whose works are considered to be masterpieces, but her subject matter and style were no longer as popular as they had been, and although her fame never faded, her works were not nearly as much in demand. What did happen, though, was that her incredible realism influenced a new generation of artists whose work was more concerned with urban life and industry. They applied her acute ‘eye” to this newer environment with the same details she applied to rural France and to animals.

Rosa Bonheur’s Style

Her style was part of what is called Realism (with a capital R) This movement came about in the 1840’s at the same time as Industrialization was taking over and there was an attempt again to have a social revolution. Instead of romanticizing nature and talking about spiritualism and religious fervor, which was what Romanticism did, Realism wanted to portray life in the most realistic and detailed, we could say, nitty-gritty way. People of all classes, in their work and in their homes and farmers and peasants in the fields, were shown going about their daily tasks. This included showing the hard parts of life, and for a largely agrarian country like France, this meant showing the animals of the farms as well as animals that were more exotic and “fashionable”.

Bonheur took great pains to show the tiniest realistic detail of an animal’s anatomy, of its movements, and of its expressions. In her works like in “Labourage Nivernois” she shows the oxen plowing the fields, and the power of her art is in how she shows the muscles and the force of these huge animals as they move across the canvas pulling the men and their plows. Nothing is prettified, even though she mastered every stroke of the brush while painting. She herself said that her inspirations and artistic influences were the painters Géricault and DelaCroix, for the graphism of their works, and Courbet for the realism of his paintings, but also she credited the magnificent sculptural friezes on the Parthenon in Greece as being a major source of inspiration. She was quoted as saying that for her, The Horse Fair, “was like the frieze on the Parthenon, an homage to the power and beauty of horses”.

She influenced painters like Millet and Daumier who also wanted to show the minute details of a realistic image.

It is in the Anglo-Saxon countries that her art had the hugest success. Even well after her style of painting had become ‘old-fashioned’, her excessive and obsessive attention to details and to realism helped inspire Anglo-Saxon artists, and the style of hyperrealism that was fashionable in the 1990’s was partially inspired by her work.

Not really forgotten, but no longer talked about as a major artist, it was in 1976, in a major important exhibit of women artists, called “Women Artists: 1550 to 1950”, put together by a very important woman art historian, Linda Nochlin, that Rosa Bonheur came back into the limelight.

This same art historian, whose work largely talks about women in art through history, wrote a very important essay called, “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?” that has become a classic. In this essay she talks about Rosa Bonheur as one of the few examples of a woman artist who made her fame and her fortune by doing art that was outside the system, and whose work fit into no category.

Who besides Rosa Bonheur has spent an entire, long life as an artist, focusing on animals? Who, besides Rosa Bonheur, dressing like a man, living like a man, and basically ignoring all social conventions, was able to be ‘free” enough to do whatever she wanted?

To quote Rosa Bonheur herself in summing up her life: ‘I am a painter. I have earned my living honestly. My private life is nobody’s concern”. Make sure the next time you go to the Orsay museum, or to the National Gallery in London, or to the Metropolitan Musesum in New York or to the Fine Arts museum of Bordeaux (among others) that you take the time to appreciate her work.

*You can see on YouTube a video that is part of the Artist Project of the Met in which a well-known American artist, Wayne Thiebaud, talks about and analyzes the painting, The Horse Fair. It is very well done in showing all the reasons why it is a masterpiece, and you can see some wonderful close-up shots of the painting. It helps explain just what was so incredibly powerful about her art.

Subscribe to the Podcast

Apple YouTube Spotify RSSSupport the Show

Tip Your Guides Extras Patreon Audio ToursRead more about this show-notes

Episode Page TranscriptCategories: Arts & Architecture, French Culture